My father was 66 at the time he first exhibited signs that something was wrong.

He was semi-retired but still working for the paint company he had retired from, and one morning, as he was getting ready for work, he found that his right hand and arm couldn't seem to master the razor or the comb and his right leg felt wooden. He kept it from my mother and went ahead in to work for his few-hour shift, where the odd feelings lingered. He lifted the coffee pot in his right hand and quickly switched it to his left for fear he'd drop it. His right leg had lost sensation so that he couldn't feel the floor against his foot. The feeling passed after about two hours and he went home as usual, wondering whether he might have experienced "a small stroke." That night, he told my mother what had happened and they decided to just see if it occurred again. After another similar but shorter episode the following day, Mom made an appointment with the primary care physician.

A CT was ordered, and the news followed: "It's a brain mass." The doctor made a referral to a neurosurgeon and an MRI was requested. At that time, we didn't know enough to be fully frightened. We believed---as many people do who are new to this experience---that a surgeon would go in, remove the mass, and judge its malignancy, then life would return to normal while we wondered whether it would ever grow back. Dad had previously had bladder cancer and recurrence, and that's the way it had worked on those tumors: pop 'em out...then stick to the checkup schedule. In fact, Dad's appointment with the urologist just a month before this had been a clear exam. So we headed into uncharted territory, and the phrase "Ignorance is bliss" couldn't have been more appropriate.

The neurosurgeon performed a biopsy very quickly after the MRI, and on June 11, 1999, all naivete flew out the hospital room window:

"The pathology report came back this morning, and the news is not good," the young neurosurgeon began. "It's a glioblastoma multiforme. There is no cure at this time, and all we can do is take steps to prolong your life."

"So...what're we talking about...in terms of that?" Dad asked with composure.

"Maybe ten to twelve months, if we pursue it aggressively."

Dad had never enjoyed jumping through medical hoops, so the question had to be asked: "What if he chooses to do nothing?"

"Three months," was the reply.

We took our numbness home with us, where it melted into a number of other things. In that first few hours, Dad alternated between planning his estate, listing those who would need to be told the news, and sobbing inconsolably, something he hated doing in front of others.

Surgery with Gliadel wafers was scheduled for five days later, June 16th, and oddly enough, we were all fairly buoyant that morning---maybe because the choices were so few, really...maybe because something was being done on the spot to rip the tumor from its home...maybe because if this went well, the doctor might, in fact, have it all wrong....

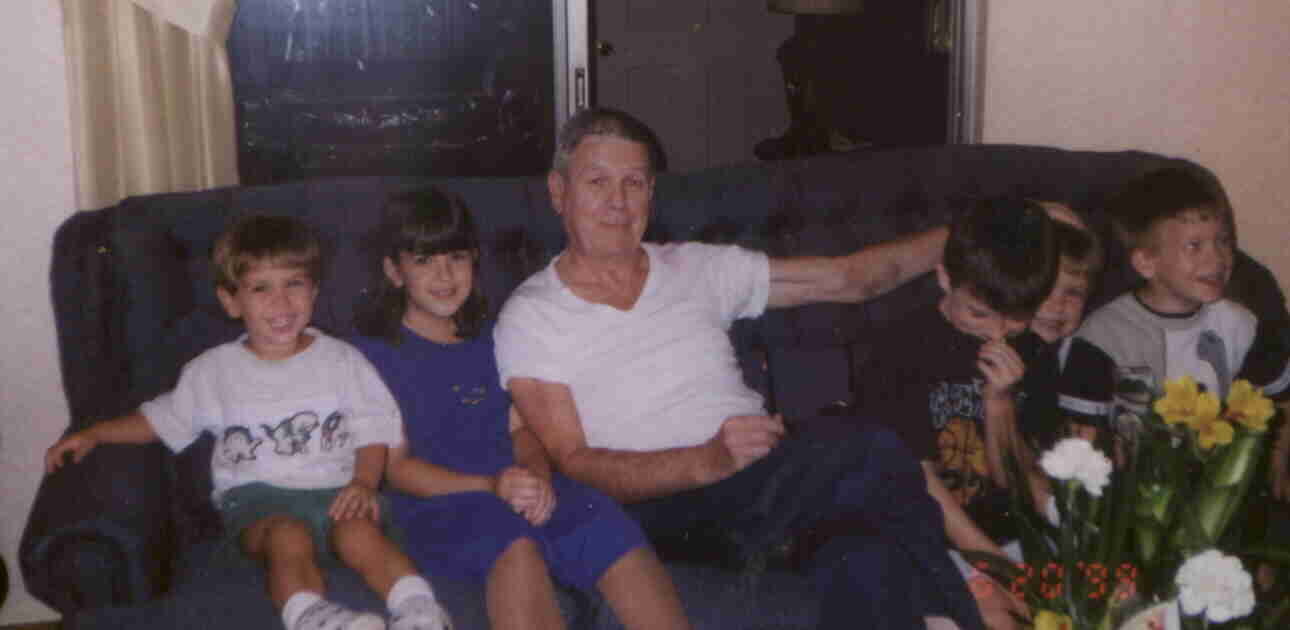

The operation took place at dinnertime on a Wednesday night; on Thursday evening, Dad was walking the halls and offered to put on a pot of coffee for the nurses during a busy shift change; he was home in time for lunch on Friday. Father's Day fell on that weekend. Would he feel up to visitors? "Sure," he said. "Bring 'em on."

Dad with his five grandkids, feeling great just 4 days after his first brain tumor resection. He had had his hair cut short in anticipation of the surgery; black-and-blue marks from IVs are still visible on the inside of his left arm.

The wound was healing nicely, and the neurosurgeon seemed pleased.

Dad began his six-week course of radiation and felt pretty invincible. He quickly learned the technicians' names and he enjoyed introducing them to us, like it was a social visit rather than a medical procedure. We had noticed that Dad's incision seemed to gape slightly in a couple of places, where it looked shiny beneath, but in the absence of fever, redness, or other signs of an infection, the neurosurgeon assured us that things were coming along as they should. But about a month into radiation---six weeks after the resection---Dad woke from a nap one afternoon to discover that his neck felt wet. Before the night was over, he had developed a mid-grade fever. The neurosurgeon wanted to see him the following morning.

Dad's wound was weeping cerebrospinal fluid, signs of a bone flap infection. The cultured fluid came back positive for staph. He was told to go home for a few things and to report to the hospital that afternoon (July 29th) for surgery to remove the bone flap. The surgery was uneventful---the bone flap (or square of bone that had served as access for the original resection) was removed, leaving Dad with a soft spot---and an infectious disease specialist then joined the medical team. A picc line was installed and Dad would need to do home infusions of one of the heavy-hitting 'cillins, every six hours 'round the clock for four weeks. Radiation would be delayed for postsurgical healing.

The infusions went easily. Mom and Dad chose 12:00 and 6:00 (a.m. and p.m.), and this was within their normal daily awake schedule anyway. Within a couple of weeks, radiation resumed and Dad completed the remaining nine daily doses on August 20th. In another two weeks, he was told he could end the infusions, since the healing was coming along well.

Two weeks after radiation ended, an MRI showed "clouds," presumed to be postrad swelling. The Decadron dose was raised, and another MRI was scheduled two weeks later, but the clouds were still there. It was a bit of a mystery until, coincidentally, Dad's head began to leak fluid once more, from places where the incision had pulled apart almost unnoticeably, like a single broken stitch along a clothing seam. Another culture revealed that the staph was back, and another emergency surgery was performed on October 4th, this time to flush out staph that was "deep...really deep this time." During the operation, the neurosurgeon took a few biopsy samples, all four of which came back negative for gbm. We had had some road blocks, but we were winning.

As with the others, the recovery from this third surgery was easy---although the infectious disease doctor was back on board and now wanted Dad to infuse antibiotics every four hours. My parents chose 12:00, 4:00, and 8:00 (a.m. and p.m.) and had a hard time with the 4:00 a.m. time slot. Since the infusions took nearly an hour to complete, it wasn't like waking up and popping a pill, then returning to bed. This exhausting schedule went on for two months, during which we moved toward the question of chemotherapy. Dad's medical oncologist leaned toward PCV, his one-size-fits-all solution to brain tumors of every type. Dad came home with a brochure about the three-chemo regimen, read it, and told us, "Forget it. I'm not doing it." Not only was he disturbed about the mentions of kidney and liver damage---after having already had bladder, heart, and now brain troubles. He also rationalized that he wouldn't eat at a restaurant with only one item on the menu, so why should he pursue treatment when only one thing was being offered? I had learned enough about Temodar, still newly approved at that time, to be encouraged that it would suit Dad well because of its mildness, so we broached that possibility with the oncologist, who reluctantly agreed to give it a try, making it clear he felt it would do nothing.

Dad took his first Temodar capsules, very nervously, on November 1st of that year. Zofran kept any possibility of nausea in check and it was a peaceful night. By the time the first round was completed, Dad felt comfortable and confident, telling his friends, "Yeah, I'm on chemo...but it's no big deal" and calling Temodar "a breeze." He was three rounds into Temodar when the MRI of January 2000 showed what the neurosurgeon called "a small something I'd like to keep my eye on." He didn't seem alarmed, so neither were we.

That same month, Dad experienced a scary time when he went from walking to walker over a period of just a couple of days. Our first thought was that the tumor may be active again after all, since motor deficits seemed to be my father's particular warning sign. It turned out, instead, that his new clumsiness was the result of a medical chain reaction! Augmentin, the oral antibiotic he had been placed on in December to wind down his staph treatment, had started an annoying yeast infection on his neck and hands, so the infectious disease doctor had prescribed Diflucan for the infection and told him to cease the Augmentin. The problem was that Diflucan can raise the blood level of Dilantin, Dad's main antiseizure medication, something the infectious disease doctor hadn't checked into. Dad's Dilantin blood level rose to 31; the normal levels should be between 10 and 20. Adjustments followed and a neurologist joined the team.

Having had three craniotomies within four months, Dad was then lined up, in mid-February, with a plastic surgeon to repair what we called the ravine on his head. The plastic surgeon was going to borrow some skin from the right side of Dad's scalp, swivel it over that left parietal area to help cover that incision that hadn't been much good, and then borrow skin from an outer thigh to replace the area of scalp on Dad's right. The neurosurgeon would be going in first, to debride dead tissue, pack in some calf tissue in order to build up the sunken area, and add titanium mesh to serve as the firm replacement for the bone flap Dad had done without for more than six months. The neurosurgeon said that he would attempt to biopsy that suspicious spot while he was in.

When the neurosurgeon came out after his portion of the surgery, he told us that he had had full access to the new growth and was able to remove it "all" once again---thereby completing an impromptu second tumor resection. The pathology report came back as gbm, but the tumor was judged to be 99% necrotic, with only a tiny viable area at its core. The neurosurgeon and the oncologist together agreed to keep Dad on Temodar longer, since, although he had had regrowth, he had also had spontaneous, almost-immediate killing of the tumor. It seemed that Temodar had been on duty when needed.

The plastic surgeon then performed his part of the surgery and deemed it a success. Dad's head was heavily bandaged at first, so we were unable to view all the work that had been done. Both doctors were quite pleased, though, and Dad was merely awaiting discharge from the hospital. Always an impatient hospital guest, Dad quickly grew restless and wanted to be sent home. The Decadron increase was also impacting his mood, making him uncharacteristically miserable and ornery. "If they don't let me out of here tomorrow," he threatened idly, "somebody around here's gonna end up with a black eye."

Apparently, he felt that---despite all warnings not to get up unescorted---if he could tell the nurses after the fact that he had done so successfully, maybe that would be his ticket home! Despite the fact that he had been working with physical therapists after the surgery and was using a wheelchair to get around the hospital halls, he was so sure he could stand and walk safely without assistance. He waited until Mom had left for the evening and no one else was paying attention, and he got up to use the bathroom. His very unreliable legs buckled immediately and as he swiveled on his way down, the back of his head hit the foot rail of the bed and from there, he fell hard onto the floor. Mom was no farther than the elevators when she realized she had left a bag in the room, so when she returned down the hall, it was to shouts of "Man on the floor! STAT!" All she could see through the many legs in the room was Dad's face, expressionless, and "a pool of blood the size of a pizza behind his head." She thought he was dead.

The nurses got him up and into bed, rechecked his bandaging, and contacted the two surgeons, who ordered an MRI. Everything looked remarkably well, considering the impact. To play it safe, the neurosurgeon ordered that Dad be placed on Ativan to calm his roving instincts, but he had been humbled by what happened and had learned the hard lesson that he needed more help than he was willing to admit.

Of course, Dad wasn't discharged the following morning as he had hoped, and ironically, the one with a black eye was him.

After another day or so, we took him home, with extensive instructions on the care of his new head graft. As the first few days followed, though, it was clear that one of the grafts was failing. While the graft over the craniotomy site appeared to have taken well despite the shock of the hospital fall, that impact had sent blood under the thin layer of skin that had been moved from the thigh up to the right side of the head, dooming any chance of its success. By now, the crescent-shaped piece of skin had turned black. The plastic surgeon peeled it up bit by bit over the weekly followup visits and then broke the news that that portion of the surgery would need to be repeated. One month later, in mid-March 2000, Dad went back in for a fairly short procedure to move another piece of thigh skin up to the head. The surgery was successful.

A home health care nurse came for a while to check on all the graft sites, and Dad continued with home physical therapy, although he professed to hate it. The therapy seemed to be doing nothing to improve his mobility or leg strength. In fact, by April or so he had gone from using the walker independently to using the wheelchair, with assistance, full-time. He needed assistance to transfer from the wheelchair to the bed and to perform bathroom duties. A bedside commode had taken up residence in the family room. For some time now, it had not been safe to shower; Mom continued to take care of cleansing Dad in the hospital bed that had now been delivered to the house. Dad was doing all his living in this one room of the house.

We also grappled with Dad's ballooning ankles and feet, trying several medications such as Lasix and Aldactazide, TED stockings, physical therapy and massage, leg elevation, and hydration to move the fluids out of his body. A Doppler ultrasound exam was performed by Dad's cardiologist and came up negative for blood clots, so we continued to just deal with this harmless inconvenience.

Dad collected clear MRI after clear MRI that spring and into the summer: five of them in a row, I believe (he had MRIs religiously on a six-week schedule). The neurosurgeon continued to congratulate him and scratch his head; the oncologist ultimately thanked us for turning him on to Temodar, telling us he had gone on to prescribe it for other patients, thanks to Dad's success with it. Although Dad didn't enjoy the lack of freedom because of the limitations on his mobility, he felt good and was enjoying an otherwise high quality of life.

At one appointment with the oncologist around May or so, we were told there was "good news and bad news." Since we would be seeing the neurosurgeon later the same day for the latest MRI report, our stomachs flipped, but he quickly reassured us that the MRI was once again clear. The bad news, however, was that, due to a family medical crisis (his newborn son had severe heart defects), the oncologist would be leaving the area to relocate to another state. He said that another doctor in the practice would assume Dad's case. He and Dad shook hands and wished each other well. (We later learned, through the grapevine, that the oncologist's young son had not survived more than a month or two.)

Later that day, at the neurosurgeon's, we asked if he had a specific recommendation of another oncologist, rather than being at the mercy of the general pool of doctors. His face lit up and he said, "There's a new guy in town. I'd love to get you in with him!" From there, Dad began with the only neuro-oncologist in a couple-hour radius---a wonderful, sensitive, up-to-date doctor who made all other specialists superfluous from that point. He kept Dad on Temodar, which was a relief to all of us after the challenge with the first doctor.

Soon, though, things began to change. Dad's vision was causing brand-new problems as he saw things double and occasionally quadruple. His legs were becoming less and less useful as we helped him with transfers and urinary duties. He was having more problems with his memory and with word finding. Otherwise, he was still mentally sharp and emotionally unchanged, although perhaps he was growing more sentimental and easily tearful, often raising his fears over "what's going to happen from here."

July's MRI showed new enhancement, so the neuro-oncologist ordered an MRS to make certain it was regrowth. The findings came back "consistent with live tumor"; Temodar was discontinued, and other options were discussed. The tumor board debated for a while but finally approved radiosurgery. Just before that, Dad agreed to switch to the aggressive chemo CPT-11, given by IV in the doctor's office. Diarrhea is to be expected with CPT-11, but Dad's case was severe. After the first dose, he had a rough couple of days. During the second dose, he was having diarrhea there in the doctor's office. It was clear he couldn't tolerate another dose of it; ultimately, he had completed only half a round of CPT-11. The diarrhea went on for more than two weeks and caused Dad to go into Depends, a miserable indignity for him. He also began to spend much more time in bed, afraid to make "any false moves" because of his problem. The inactivity gave Decadron more opportunity to work on his already wasting thigh muscles, and over those idle weeks, his thighs withered visibly.

X-knife radiosurgery was scheduled for September 19th, and Dad was by then not strong enough to be brought in by wheelchair, since his legs could support no weight at all. A medical transport van was called out to the house, and Dad teared up when the men came in to move him onto the gurney. He had been afraid of radiosurgery; for some reason, he had himself more worked up over this procedure than any of his five head surgeries over the past 15 months. Once the head frame was on, though, he relaxed a lot and soon it was over and he was back home, resting. We were told that his tumor, roughly 3 cm cubed, was ideal in shape, location, and size and that it was one of the easiest radiosurgeries they had ever performed.

We waited for Dad to regain some strength so we could get him back in to see the neuro-oncologist, as there was no way we could have him brought in through the waiting room by gurney. He never did improve, though he was still sharp verbally and mentally those days. He was bedridden now, needing some help with certain meals like soup, and he was beginning to sleep more and more---long naps with breaks in between that didn't coincide with Mom's sleep schedule at all. She was exhausted.

By the end of September, Dad had started something new. He was extremely agitated and fought sleep in a way that was supernatural. Over one five-day period, he had slept perhaps three hours total. He talked almost nonstop, alternating between crocodile tears, shouts, threats, obscenities, and simple requests to get him "out of this nursing home." He couldn't bear for Mom to be out of the room for more than a few minutes. Once, when she dozed at his side with her chin in her hand, he woke her in a panic, afraid she would leave him. When she wasn't paying enough attention to him or left the room to prepare a meal or use the bathroom, he would rudely bang his wedding band against the bed rail or flick the nearby window blinds roughly with his hands. No matter what we tried, we couldn't get him to sleep. He had taken in very little food those days and drank only a little when it was offered.

We had talked to the neurosurgeon when this began and he had Dad begin Ativan, but after a couple of days with no change even with extremely high doses, he was switched to Haldol and we were told it would take several days to take effect. It was clear that Dad wasn't going to become strong enough for further chemo---nor would he be interested---so on October 2nd, hospice came out to meet us and take a medical history. This decision that we had always feared ended up being an easy one. As is true with so many things, the really important decisions often make themselves, with very little need for debate from us, if we are honest with ourselves.

Within a few days, Dad was calm and comfortable, resting easily even with people in the room, back to his normally polite, gentle self. He was no longer interested in food at all and was only taking maybe a few teaspoons of pudding or pie filling in order to get his Decadron in. We had gone to suppositories for the too-large Carbatrol for seizure control. He was no longer accepting much by way of liquids. About four or five days before the end, he had consumed his last water, and prior to that, he had started to merely pretend he was drinking, for our sakes.

He probably said his last words two to three days before the end. The day before, he winked and wiggled his fingers goodbye to me as I left for the afternoon---the last communication I had from him. The hospice nurse was with us and said his vitals and his lungs sounded great. By now, he was finding it hard to keep his eyes open, so it was hard to tell whether and when he was sleeping, but he was extremely relaxed and seemed happy and at peace, smiling often at us.

On the final day of Dad's life, October 10th (just eight days into hospice care), Dad was unresponsive the entire day, even to requests for hand squeezes. The hospital chaplain came out and ended up saying a prayer with us in Dad's presence. After kissing Dad's forehead while he slept, I went to leave for the day, but something made me turn back. I had dreaded this thing I knew I would have to do sometime: I had to tell him goodbye not just for the day, but forever. I thanked him for the wonderful childhood, for all the sacrifices he had made as a parent, and for the college education. I told him I was proud of him for all that he was, especially for how hard he had fought. I said that I understood how hard it was to fight now, and that if he felt it had become too much, he could stop if he wanted to. No one would be disappointed in him. He would not be letting us down. I promised that I would make sure that his grandchildren knew him and that everyone was looked after---his mother in the nursing home, Mom, my sister, all the grandkids. He could trust me to make sure that Mom especially would be looked after. Then I told him I would see him again tomorrow and I kissed him again.

Later that night, Mom sat by Dad's side telling him repeatedly what a wonderful husband and father he was. She held his hand and kissed him often and just stayed there for hours, even when the raspy breathing, called the death rattle, began. Mom called me and I could easily hear it over the phone. I knew, from all I had heard, that time would now be short, so I told her I was on my way (from an hour east). I told her to call hospice and alert them. I drove as quickly as I could but I was about a half-hour late for his passing. Mom said that at 10:12 p.m., Dad's eyes opened suddenly as if he had been startled by a loud sound, he looked at her, and then his eyes fell to the left. A completely peaceful departure, with just the two of them, as it had begun with their marriage a long time ago.

Hospice soon arrived, did some paperwork, and dispatched the funeral home. It was amazing that Dad's bloated appearance began to fade very quickly in the time that followed. He looked relaxed and at peace.

My sister arrived next, and we waited together for the funeral home. The two men arrived around 1:30 a.m. and quickly and discreetly handled removing Dad's body from the house. Then my sister exclaimed, "The tape!" We all knew right away what she meant. I had given Dad a microcassette recorder the previous Christmas, to help with both his shorter memory and his difficulty in learning to write left-handed. But he had never used it to record notes to himself. Or at least we didn't think so. The previous January, back when he was experiencing the Dilantin toxicity and he feared "this was it"---a full nine months before the actual end---he had sat and recorded a final message for us, his "girls."

We easily found the tape in the predictable catch-all cabinet where Dad kept batteries and such. We set it in the middle of the family room floor and listened in the semi-dark as Dad told us how much we meant to him...how proud he was of us...how he had made the perfect choice in Mom, who was his buddy...how even though he wasn't always that vocal with the "I love you"s, it didn't mean he didn't love us...because he did...and several times he said that in looking back over his life, he had no regrets at all. "No regrets...," he told us. "If I had it to do all over again, I wouldn't change a thing."

The tape clicked off on his final word. He had said everything that meant anything to him at all and it was what he wanted to leave us with. What a gift that as his body left this world and then left a house he had loved, his reassuring voice could tell us how pleased he had been with how it had all played out.

It has occurred to us since then that we are also without regrets...because we loved him and weren't afraid to show it...because we stood up to that merciless tumor alongside him and helped him find all the tools for the fight...and because when it came time to find peace, we helped him find that too...and it was our honor to do so.

This site is dedicated to my wonderful father and friend:

Edward M. Robinson, Jr.

January 12, 1933-October 10, 2000

diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme on June 11, 1999